What is Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)?

Read other articles:

Back to posts

Table of Contents

Content and language integrated learning (CLIL) teaches content in the target language, allowing learners to acquire the language through the material rather than through direct language instruction.

CLIL disrupts many traditional language teaching methods. There are no textbooks, no grammar, no vocabulary lists, and no flash cards. In fact, language teaching per se goes out the window!

Instead, students might learn about how to cook omelets in Spanish, the history of the world in French, or how to ski in German. The positive results of this approach have been well-supported by studies.

Any subject is fair game as long as it’s engaging and delivered in the target language rather than the learner’s mother tongue.

Let’s take a closer look at content and language-integrated learning, why it’s beneficial for language learners, how it connects with Dr. Stephen Krashen’s second language acquisition theory, and how to incorporate the CLIL approach in your learning:

- What is CLIL?

- CLIL is NOT a type of language class so how does it work?

- Pros and cons of the CLIL approach

- CLIL and Krashen’s theories of language learning

- Where do you find content to learn from?

What is CLIL?

Rather than simply learning a language, CLIL is like learning through a language.

Professor David Marsh of the University of Jyväskylä in Finland developed this approach in the mid-1990s, drawing heavily on concepts used in language teaching for decades.

The two most important concepts in CLIL are:

- The target language is the medium of instruction

- The subject is more important than the language

The CLIL method integrates these two essential elements: the subject matter and the medium are inseparable, with students benefitting language-wise because of their interest in the topic.

Contrast this with more traditional language teaching methods that are led by instruction in the mother tongue of the students and focus on the language itself rather than interesting topics. This type of approach has no place in CLIL.

Let’s say a group of English-speaking wine enthusiasts want to learn Portuguese. The content used to “teach” would need to be in Portuguese and could be on any subject that will engage the learners.

It might be:

- What dishes go best with Portuguese red wines?

- The main wine regions of Portugal

- Top 5 vineyards around Lisbon

- History of winemaking in Portugal

With CLIL, learners don’t need to actively study the language. Instead, they absorb or “acquire” the language almost passively while researching and learning about a subject in the target language—ideally from native speakers.

For this to work effectively, learners must stay highly motivated. Motivation plays a crucial role in language learning, and in CLIL, passion for the subject drives the learning process.

Learners acquire the language in context when they have a genuine interest in the subject. Often, they face challenges, scratching their heads and wrestling with meanings. These efforts ultimately help the language “stick.”

CLIL is NOT a type of language class so how does it work?

CLIL is based on language acquisition rather than enforced learning.

It’s best not to think of CLIL as a way to teach languages or a language class. The subject is the most important element of the class and language learning happens as a by-product of learning about the subject.

Students learn naturally, similar to how they learned their mother tongue as children.

Consider how many people around the world have picked up basic Japanese from their interest in watching Japanese anime cartoons or reading manga comic books. These popular forms of content have a large following in the West as well as in Japan—and have inspired many to learn the language in a natural way that remains long after the comic books are put down.

Because the language in the manga is generally quite simple and the comics have interesting storylines, they hold attention. It’s relatively easy to follow what’s going on from the pictures, making manga a great way to learn Japanese—and CLIL works similarly.

With CLIL, students can effectively acquire a new language even when the material exceeds their proficiency level. Repetition within the subject matter and visual cues, such as videos or other visual prompts, reinforce understanding and support language acquisition.

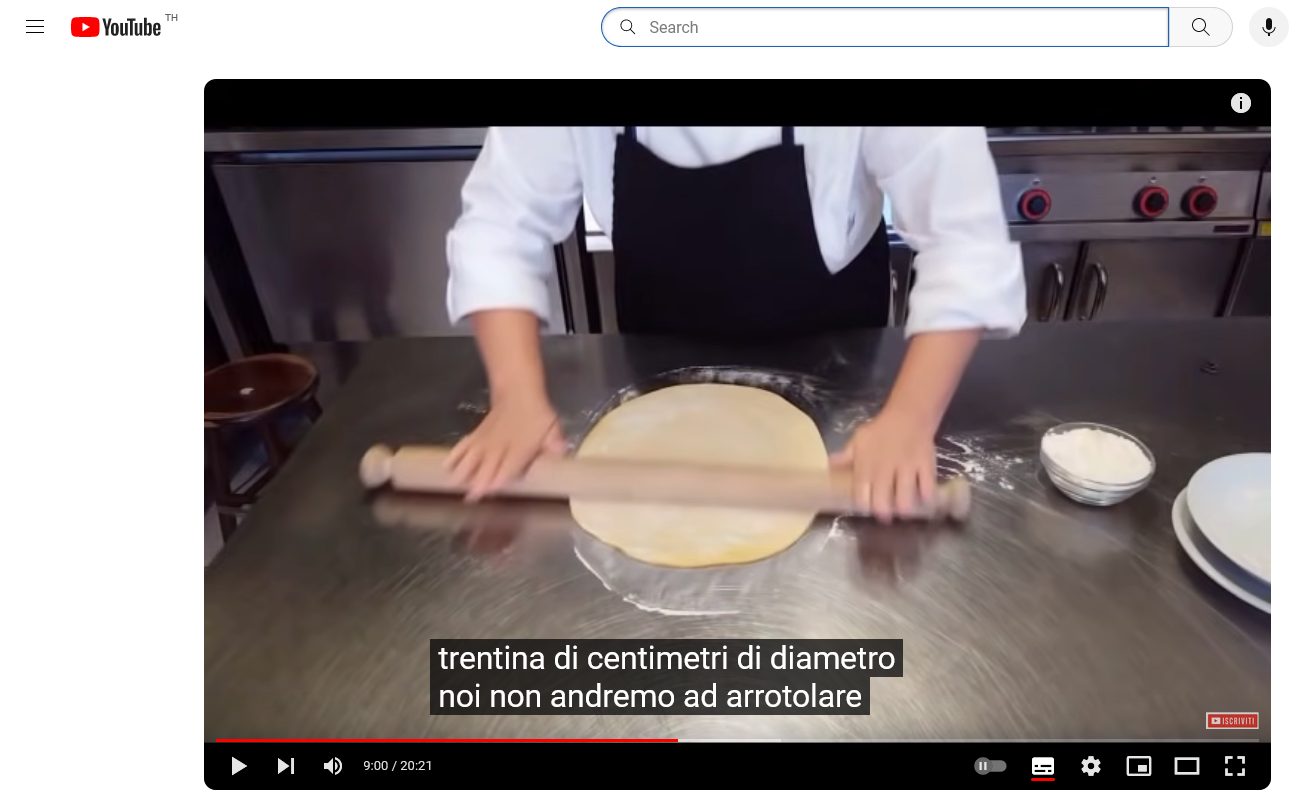

For instance, a group of English-speaking Italian cooking students are learning about how to make pasta in Italian. They will quickly learn the words mattarello (rolling pin) and tirare (the verb to roll) even if they don’t know the words when the instruction starts.

New language forms, vocabulary, and grammar are learned naturally—without any teaching focusing on the language itself. There’s no work on sentence structure or verb conjugation rules. The language is acquired from the context. This is fundamentally how CLIL works.

It’s interesting to note just how many people who speak their native language to a very high level would struggle to explain the grammar rules if asked to do so. That’s because we don’t learn our native language like that. We learn from seeing the language in action. So, why shouldn’t we learn a foreign language like that?

Pros and cons of the CLIL approach

Content and language-integrated learning has several important benefits over traditional grammar-based language learning:

- Helps to introduce learners to the wider cultural context

- Improves overall and specific language competence naturally

- Learning in context is more effective (more memorable) than rote learning

- Easy to remain motivated to learn

- The acquired language is relevant and meaningful to the learners

The main drawbacks of the CLIL approach are the challenge of finding teachers with the necessary subject knowledge and the lack of CLIL teacher-training programs. Teaching the subject at the right level of language usage can also be a challenge. CLIL works best when the language is matched with the proficiency level of the students so that they are not left scratching their heads or hopelessly bored.

The language can be more advanced than the student’s current proficiency level, as visual cues provide support. Skilled teachers can also emphasize key language through repetition to ensure clarity and avoid confusion.

When using video for self-study, learners can pause and replay sections multiple times to catch any missed language and reinforce understanding.

CLIL and Krashen’s theories of language learning

Stephen Krashen famously said, “Language acquisition does not require extensive use of conscious grammatical rules, and does not require tedious drill.”

Krashen often refers to how children “acquire” their mother tongue in his language-learning theories—without knowledge of grammar, rules, and structures.

Children learn by interacting with mom and dad, listening as adults talk to each other, watching cartoons, and so on. They’re usually already fluent by the time they start school without having had any formal language instruction.

This understanding has underpinned Krashen’s theories, which can be summed up in the following way: Language is most effectively acquired by highly motivated learners receiving comprehensible input on compelling subjects in anxiety-free environments.

At times, when grammar lessons appear to be effective, Krashen says, teachers and students are deceiving themselves:

“They believe that it is the subject matter itself, the study of grammar, that is responsible for the students’ progress, but in reality, their progress is coming from the medium and not the message. Any subject matter that held their interest would do just as well.”

CLIL closely follows these beliefs. It is most effective for motivated learners who are passionate about the topics they’re studying and who acquire the language naturally from the content “input”. Often, because of the great interest in the topic, students might even forget that they’re learning a language.

With both approaches, reading and listening are the key skills involved (input) rather than speaking and writing (output). This is especially important for learners who are not yet confident when using the target language.

Also, language fluency is more important than accuracy in both approaches. Errors are considered a natural part of language learning.

Ultimately, there are many elements of Krashen’s work in CLIL philosophy—the two approaches are closely related.

Where do you find content to learn from?

CLIL methods have been found to boost vocabulary, understanding of grammar, and conversational skills without focusing on these elements of learning.

However, it can be tough for teachers in classroom settings to find subjects that classes of students are interested in and that they know enough about to teach.

How can you provide meaningful content that resonates with learners and fuels their learning naturally? And what about learners who don’t have access to a CLIL-inspired classroom and teacher?

The good news is that you can learn a foreign language without a language teacher using the CLIL method.

Whether you’re a water sports fanatic who also wants to learn Hungarian or a movie buff who wants to learn Greek, the CLIL method can work with self-study. Effective learning through CLIL starts with identifying topics of interest that motivate you to learn and have content available in your target language.

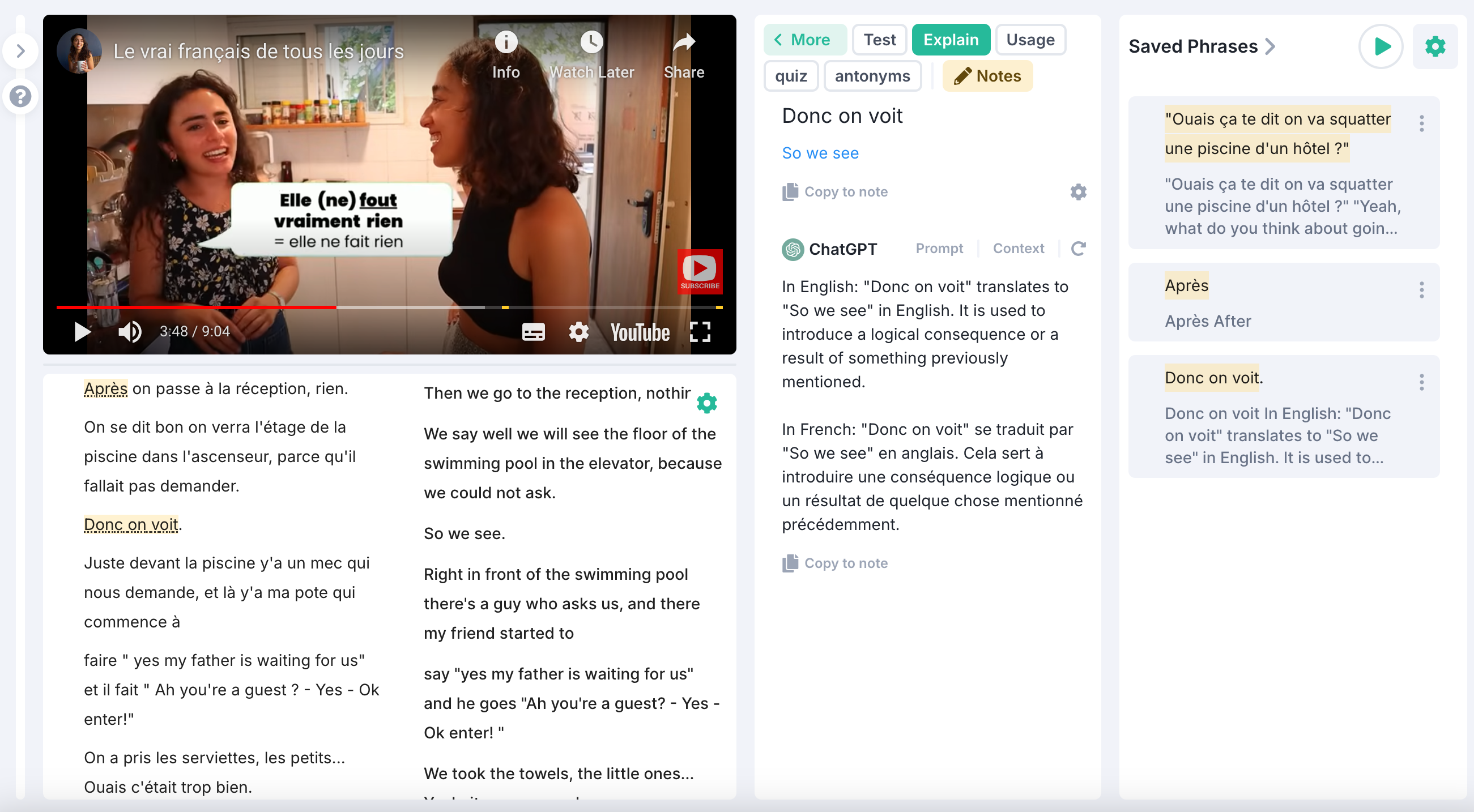

The obvious place to find this content? YouTube. There are hundreds of millions of videos available there on every conceivable topic and in every language on the planet…

Try out this free language app to learn languages from YouTube videos

Our free app is designed to help you learn your language from YouTube videos out of the classroom and at your own pace.

Watch YouTube videos in the target language on your favorite topics and build a comprehensive language library of relevant vocabulary and phrases simply by watching native speakers in context. Try now.

Read other articles:

Back to posts